What do I know about AI? Next to nothing.

So why would my colleagues at the American College of Physicians invite me to speak in a panel discussion on AI in primary care? It was a mystery to me and yet I agreed, because hey, I like feeling wanted. And I trust my ACP friends. They know me and they knew what the panel needed.

The meeting was this week. Daughter got sick, Husband was out of town, and I chose to stay home. I thought, ‘Nobody will miss me, I don’t know anything anyway.’ But through the wonders of technology, I was able to participate via Zoom, yay! And I did end up contributing, as the one clinical physician panelist. It was fun and connecting, despite my being remote. I recognized two former colleagues during Q&A just by their voices, and another texted me from the audience after she saw me on screen. This technology Luddite may yet be converted.

I share here a summary of my learnings and perspective on AI in medicine at this moment—I have many more thoughts about it than I realized! I wonder how long before it all changes? I bet not as long as I think.

Current State

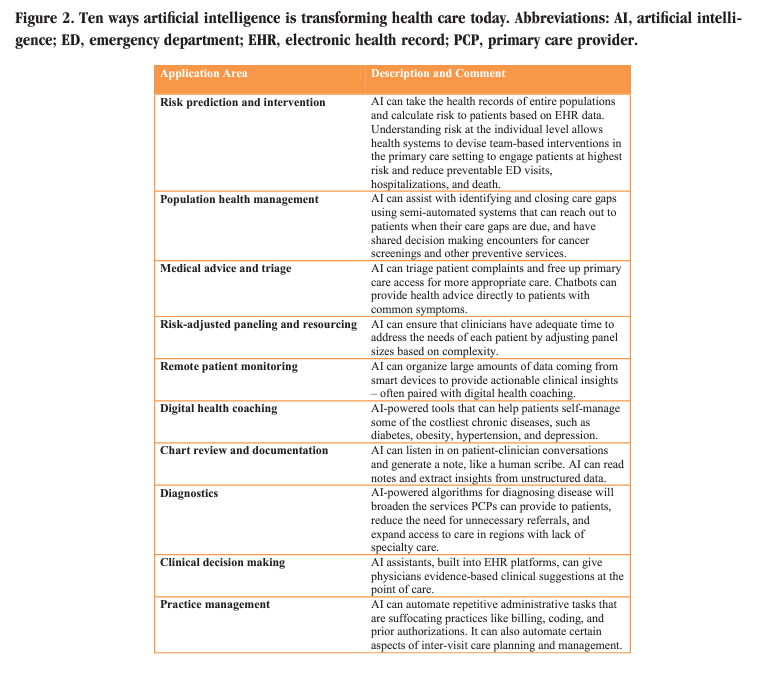

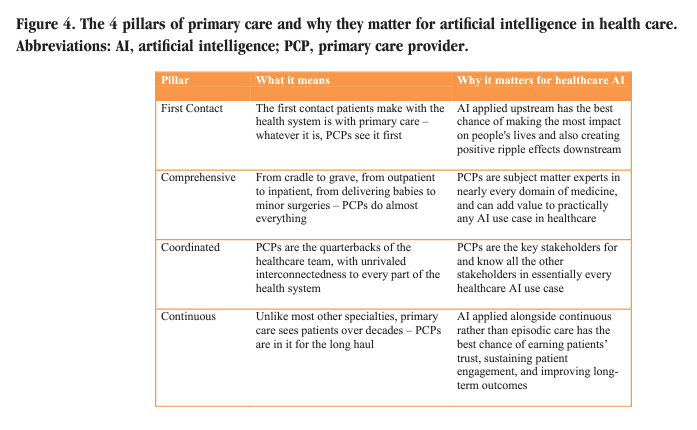

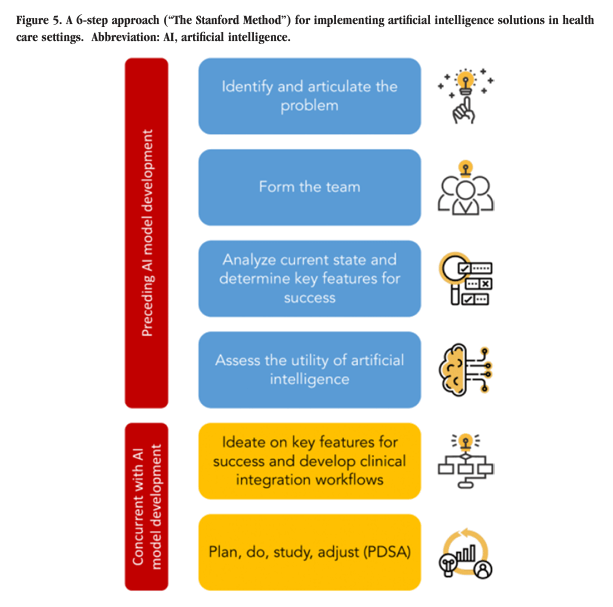

Dr. Steven Lin is now my favorite clinician writer on the possibilities and pitfalls of medical AI, and in primary care, specifically. For two excellent and concise summaries, read an internal Stanford interview from 2019 and his original article from the Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine in 2022. Some visual highlights from the latter:

Mission: To Enhance, Not Replace, Human Care

Intelligence is complex, and none more so than the human. We are amazing! For simplicity’s sake let’s just divide human intelligence into cognitive and limbic—thinking and feeling. Intuitively we probably all understand that ‘artificial intelligence’ refers to the former, activities that can be replicated using concrete and objective data and logic. Algorithm implementation and machine learning already enhance diagnostic accuracy, clinical decision making, and risk assessment and management. AI even delivers health coaching now, with encouraging results. Triage, access, billing, and follow up processes will all likely improve in the coming years with AI. I welcome the streamlining and appropriate simplification of our enragingly labyrinthine healthcare systems.

Still, patients will always need personal encounters with clinicians who provide services and care. But when were you last able to reach your primary care provider directly and quickly? How long do you have to wait for an appointment when you’re sick? If you answered, ‘recently’ and ‘not long,’ you are in the vast minority. How well does your primary care doctor know you, if you have one at all? So many patients have given up on establishing this bedrock healthcare relationship, because the system makes it next to impossible for you to talk to me when you’re sick, my schedule is booked solid for three months so I can’t see you anyway, and when I do see you, I only have 15 minutes. It’s like speed dating with earplugs and snorkel masks.

AI will never know and interact with humans on an emotional, relational level. What it can do is remove the transactional, clerical, algorithmizable(!) tasks from clinicians’ plates, so we can sit and talk with you, see and know you as a whole person, and care for you in the most personalized ways. AI can learn which of you has a lot going on medically, who needs extra time and attention. But only a human can deliver that attention in a way that truly cares for and heals you, especially if your health needs are complex. And the more AI shows us what’s needed, I suspect we will need many, many more intellectually, emotionally, and relationally competent clinicians in all fields to answer the call, which is a whole other mountain unto itself.

Data: “Garbage In, Garbage Out“

Applying populational data to individual decision making has always been both science and art. AI can enhance this very personalized activity by making vast amounts of data easier for clinicians to access and interpret in real time patient care. But beware big data: How is it collected? How do we measure and confirm its accuracy? How is it entered, organized, aggregated, interpreted, used? Who decides all of these things, and what interests do they have? Who will monitor for bias, equity, and unintended adverse effects on certain populations that are inherently, if inadvertently, built into AI systems at the level of design? This is where I really see us falling down and not even knowing, and then ignoring and dismissing those who call it out.

Governance: Honest, Transparent, and Accountable

After we answer the question of who will monitor, we must ask and answer how. The American healthcare system is fundamentally capitalist and increasingly consumerist, an extremely high-risk combination. Bad actors will certainly subvert the mission of individual and collective health and well-being to make more money. But possibly more dangerous are those who honestly believe they are out to help people and who, despite their best efforts, succumb to economic and cultural pressures to put profits (or market share, or personal status, etc.) ahead of professed altruistic mission. Short term financial and social costs of inventing, experimenting, and iterating innovation can be intolerably high, and too often those in power and regulatory positions act on primal (though well-rationalized) instincts to forgo those costs to protect and advance other interests. At our core, we humans are emotionally driven decision makers who then justify our actions (often vociferously). Only when we accept this reality can we hope to regulate our systems honestly, transparently, and with true accountability. I feel deeply cynical about the likelihood of us doing this at all effectively.

Agility and Evolution: Lightning vs. Glaciers, Integrated Co-Creation, and Emergence

Technology moves increasingly at lightning speed; medical knowledge doubles now about every 4 years, compared to every 50 years in 1950. Medical culture, on the other hand, moves at a glacial pace. I’m thinking of gender and racial equity, holistic mental health, and mind-body awareness and practice. To avoid harms and fully benefit from the inevitably rapid evolution of AI, we must build systems that foster invention, experimentation, and iteration at local nodes (team, practice, department, hospital, health system, etc), strengthen multidimensionally integrated and transparent internodal communication structures, and maintain monitoring processes that can detect common, coincident AI benefits as they emerge, so they can be efficiently, effectively, and appropriately scaled. At the same time, solutions must be flexible enough to adapt and iterate on a global level, as shared learning marches onward. This open-source and resource-intensive style of collaborative innovation feels antithetical to the competitive, short term profit-driven American healthcare business culture. I see this challenge as especially inextricable from the accountability problem of AI governance above. Yikes.

Medical Education: Leading and Learning by Example

Sometimes I wonder if technology is making us all dumber–like maybe safety features on modern cars makes us fundamentally less mindful drivers? We clinicians all have Google and UpToDate at our fingertips; accessible information 24/7. Almost every day, I look things up in real time during a patient encounter—did you know some people grow more lipomas if they drink more alcohol? There is just too much information now to keep it all in my head. I feel comfortable thinking out loud with patients, talking through basic physiology and how it may relate to or explain their symptoms. When I come across something novel or atypical, as long as the patient is stable, I feel a little exhilarated, like we’re going on a themed scavenger hunt for diagnosis and treatment. This is exactly where AI can optimize care, by gleaning the vast seas of medical information and knowledge, filling the gaps in my head that will only get larger over time. It gives me more bandwidth to ask better questions, listen longer to patients’ answers, and explain increasingly complex plans of care better.

Having trained on the cusp of the information age, I wonder how/whether my thought processes differ from, and how that affects my relationship with, younger docs? Medicine has always been an apprenticeship profession, and we have always felt social generation gaps that mirror society at large. I think that will not change. What has changed–narrowed–is the information/knowledge gap. 20 years ago, my teachers consistently knew exponentially more than I did about almost everything. I think those days are long gone. Any student today who just rotated through any given medical subspecialty will know more than I do about new diagnoses, drugs, and procedures. I am totally okay with this–there is so much to learn, I should get it wherever and from whomever I can.

Teachers and mentors, however, hold experience, intuition, context, and judgment that can only come with cumulative time spent in practice. This is what we have to offer our trainees–the example of curiosity and humility for lifelong professional and personal learning. As AI accelerates and infiltrates our systems, teachers must role model critical openness, mission- and relationship-centered integration, and an agile, honest, growth mindset. None of us will ever now know it all. Optimal patient care merges expert knowledge with presence, attunement, wisdom, and connection–machines cannot do or teach this, and we must all help one another figure out how best to incorporate machines into patient care.

Cautious Optimism

Primary care has the greatest potential and privilege to see, hear, and touch every other medical specialty, and all aspects of the healthcare system at large. Wow. How could I not love this work? What fascinating and rewarding polarities to navigate–tradition and innovation, conservation and progress, intellect and relationship, strategy and vocation. I have no complete (or even well-formed) answers, only reflections. I know where my values and goals live, though, and I root down to them. If we can do this as a profession and a society, then AI’s potential to make all our lives better could be limitless.