Have you ever been in an argument and suddenly realized the perfectly mean thing to say, that ultimate verbal weapon that would render your opponent categorically mute and ambush them into abject submission? It’s an exhilaratingly powerful feeling, isn’t it? What did you do? Did you bite your tongue and take the high(er) road? Did you blunt the skewer and lob something passive-aggressive instead? Or did you let loose that ax with the full force of rage behind it, just to see what would happen?

***

I had another convergence experience last week, in a series of articles on my Facebook newsfeed. It started when I saw this piece on reconciling the parts of ourselves which we subconsciously hate, in order to live more integrated, fulfilling lives, particularly in our relationships with others. The author discusses Carl Jung’s core ideas, stating, “To heal a split in self, a person needs to work with their shadow and learn uncomfortable truths about themselves in the process. Our inner war is softened when we allow ourselves to be seen. Not just the side of ourselves that matches our intersubjective ideal — that is easy. We show those feathers prominently. No, we need to accept our failures and shortcomings too.”

Yes, I know. It’s the Sh*tpile all over again.

The Remembrance

I attempted to read a book several years ago, Debbie Ford’s The Dark Side of the Light Chasers. There is an exercise on page 69 of the 2010 paperback edition in which she lists a set of negative words, such as greedy, phony, cheap, lazy, wimp, fat, passive, coward, etc. The instructions are as follows: “Identify the words that have an emotional charge for you. Say out loud, ‘I am ________.’ If you say it without any emotional charge, then move on to the next word. Write down the words that you dislike or react to. If you are not sure…ask yourself how you’d really feel if someone you respected called you this word. If you’d be angry or upset, write it down. Also…(think about) words that are not on this list that run your life or cause you pain.” The list is almost two pages long.

Back around 2011 I did this exercise in earnest. I wrote down words like controlling, bitchy, rigid, egocentric, better than, arrogant, defensive, judgmental, condescending, oversensitive, and many more. I’m looking at the list right now, written on a napkin while I sat alone reading at lunch—so long and depressing. Who knew I hated so many things about myself? I got through another 40 pages of the book, as evidenced by the bookmark still wedged at the end of the chapter entitled, “Embracing Your Dark Side.” All I remember is the profound, visceral discomfort I felt after that exercise, the unshakable fear and shame, and how I basically came home that day and picked a fight with my husband that lasted for two weeks. Not my proudest moments on this journey of self-discovery…. I remember thinking, ‘This is f*ing hard. How will I ever get on the other side of it all?’

These days, things feel very different. I’ve done a lot (a lot) more inner work, studied and learned, and enlisted professional help to overcome my aversions to emotional vulnerability. I’m thinking I could probably pick this book up again, redo the exercise, and have a very different experience.

The Emergence of a Thread

While I pondered this, another article came across my newsfeed, entitled, “What Nice Men Never Tell Nice Women.” Basically it describes the internal tension between men’s competing impulses: “The nice man is democratic, egalitarian and deeply sympathetic to the feminist agenda – and yet in sexual fantasy, he loves the idea of being tyrannical, bullying and really very rough. He himself can’t understand the disjuncture between competing parts of his nature; he is spooked by the drastic switch in his value-system that occurs the very second after orgasm.” Wow.

The article concludes with, “It’s clearly very hard for the partners of the nice to take on board the darker sides of their lovers. But if they are robust enough to dare to give them some attention, the result can be an extraordinary flowering of the relationship beyond anything yet experienced. However close we may be to someone because they have been nice to us, it’s as nothing next to the closeness we’ll achieve if we allow them to show us, without shaming or humiliating them, what really isn’t quite so nice about them.

“Out there, in the politer corners of society, nice guys are – without saying a thing, that’s not their style – waiting for nice women to start to gently take the weighty burden of their ‘badness’ off them. And, of course, vice versa too, for no gender has any monopoly on the sense of being bad.” This last sentence gave me pause and hope. It turned the tables and made it okay for women to also have a dark side, for us to also struggle with our ‘niceness.’

One of my friends commented, questioning, “So all men are either openly hostile and misogynistic, or are burying their dark feelings?” I almost reflexively I replied, “I took the article as saying we all bury our dark feelings somewhat, and we can live fuller, healthier lives if we both acknowledge them and manage them effectively.” Again, I found myself returning to this core idea of grappling with our inner demons. By now I started to wonder about cosmic timing. What has the re-emergence to teach me now? We all have some base impulses, parts of ourselves that we would sooner deny than acknowledge, let alone show to the world. I wrote about this, rather spontaneously and unexpectedly, at the beginning of the Blogging A to Z Challenge. Little did I know then that this would become a recurring theme this summer. It’s as if the universe urges me onward, perhaps sensing that my motivation to dig in my shitpile wanes, when I ought to be digging deeper, integrating more? Isn’t this what I’m always preaching, to Own Your Shit? Okay then, I thought, I will stay on the path.

The Dark Side of the Dark Side

The next article to converge on this shadow-themed week came in the form of tweets by a reporter from a Trump rally on August 18th. People were saying Hillary Clinton should be executed, calling her a ‘f*ing witch,’ calling President Obama a ‘goddamn Muslim terrorist,’ saying ‘reporters need lobotomies, and maybe that’s what Trump will do after elected,’ wanting to ‘hurt the press,’ mentioning ‘a civil war if Trump loses,’ and it goes on. It occurred to me that these are examples of us not managing our dark sides very well. The article on Carl Jung and Debbie Ford’s book both embrace the idea of uncovering our less generous traits with compassion, and integrating them for a healthier whole. These people’s behavior, by contrast, demonstrates the profound risks of allowing those darker impulses to overtake our consciousness, words, and actions. The container of repression has its limits. When someone outside applies incendiary words and rhetoric, the fire drives internal pressures beyond the container’s capacity. If that person then provides a release valve in the form of a similarly aggravated group, well, violence and mayhem are born.

In my previous posts I have reminded myself to remember to look beyond the mob mentality, and listen for the individuals’ personal experiences. I have to continuously remind myself that we must have more in common than not. We are all human, after all, and we love our country. So what could drive people to abandon all social norms of restraint, and unleash such profound loathing into the world?

I came across the final piece in the convergence on Sunday, which offers some insight. Veteran journalist Joel Stein wrote this blog post exploring the nature of internet trolls. In it he describes how despite the profoundly abhorrent things these people may write to their online prey, they are not the dregs of society that we may imagine. He quotes a social media exec: “’The idea of the basement dweller drinking Mountain Dew and eating Doritos isn’t accurate,’ she says. ‘They (could) be a doctor, a lawyer, an inspirational speaker, a kindergarten teacher. It’s more complex than just being good or bad… It’s not all men either; women do take part in it.’ There’s no real life indicator,” he writes.

Stein describes his experience confronting his own troll of two years, a 26 year-old, small-framed, female freelance writer who on multiple occasions tweeted that she wanted to “kick (his) ass.” He invited her over Twitter to meet for lunch in order to confront her, and she cheerfully agreed over email. Excuse me?? During the meal she admitted that she was just lashing out at what she perceived as his ‘smarminess,’ and told him outright, “’It’s clear I’m just projecting. The things I hate about you are the things I hate about myself.’” And though she had been trolled worse than he, she experienced no sympathy that prevented her from doing it to him. She expressed incredulity when he asked why she never carried out her threats to beat him up, even when she had the chance. “’Why would I do that?’ she said. ‘The Internet is the realm of the coward. These are people who are all sound and no fury.’”

So more and more, in both large, impersonal groups and online, our dark sides are given free reign with few, if any, meaningful consequences. Under cover of the mob and anonymity of the internet, we can freely relieve our repression. But it comes without any insight, and there is no lasting benefit, for ourselves or those around us. There is only offloading, a temporary pressure release, only to continue re-accumulating, with unpredictable and potentially very destructive outcomes.

This is not, I think, the manner in which Carl Jung envisioned us coming to grips with our shadow selves. This is not integration. Rather it is advanced separation— perpetual splitting of self from self and from others.

The Lesson

So what have I learned? We all harbor coarse, corrupt, even barbaric tendencies. We are descendants of cavemen, after all, and still hardwired as such in our limbic brains. Still, most of us exercise discretion and civility in everyday life, and find ways to get along in society—we exert neocortical controls. Every once in a while, though, something gets the best of us, catches us off guard, and the ugly slips out. Sometimes it’s pretty scary ugly.

Once again, I conclude that shaming ourselves or one another for the repugnance is the opposite of helpful. Just like the offloading behavior that incites our disapproval, automatic ad hominem negativity toward perpetrators of such words or acts only serves to further alienate them, adds fuel to the fomenting rage fires. When we berate ourselves for our shortcomings, we make ourselves smaller and less resilient–more likely to react with rage rather than respond with gentleness.

In the end I think it’s about judgment. We can and should judge which attitudes, policies, and behaviors we deem right and good. At the same time we should exercise caution and extreme patience when we find ourselves judging ourselves and others on worthiness. The default assumption must be that we are all worthy, that we all deserve a voice, no matter how vulgar and objectionable our words. We must apply boundaries, and we should expect mutual respect and tolerance; we can find ways to deal with disrespect and intolerance that do not invalidate one another’s innate humanity.

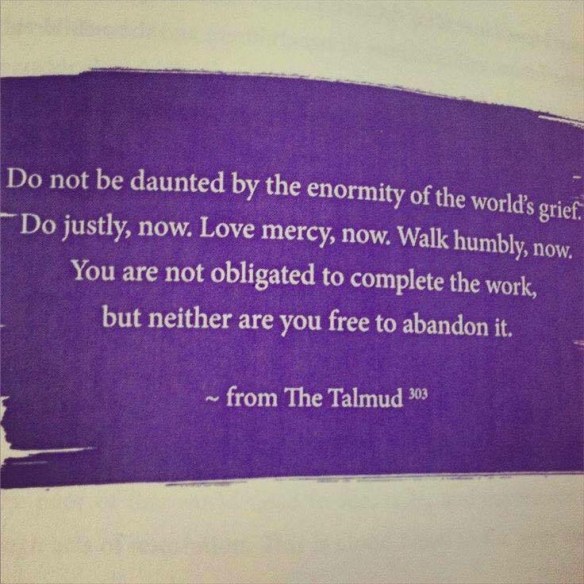

As we each pursue our own inner work, dig in our respective shitpiles, we contribute to the life gardens of those around us, and lead by example. It can be back- and sometimes spirit-breaking work. But we must continue. There is too much at stake for us to take the path of least resistance, the path of separation and alienation. Let us stay on the more demanding and more rewarding path together, friends–the path of connection. Let us hold one another up through the shadows, and seek always the light within each and all of us.