NaBloPoMo 2017: Field Notes from a Life in Medicine

What tribes do you belong to? How do they serve you, and you them? How not?

I think of this today as I have traveled out of state to speak to a Department of Surgery on physician well-being. I wonder how often they have internists present at their Grand Rounds? What a tremendous honor, I’m so excited to be here! I hope my talk will be useful and memorable, as I represent my field and my institution, in addition to myself. In the talk I describe the central tenets of Tribal Leadership and culture, and how to elevate ours in medicine.

So I’m thinking tonight about tribal pride and tribalism—the benefits and risks of belonging.

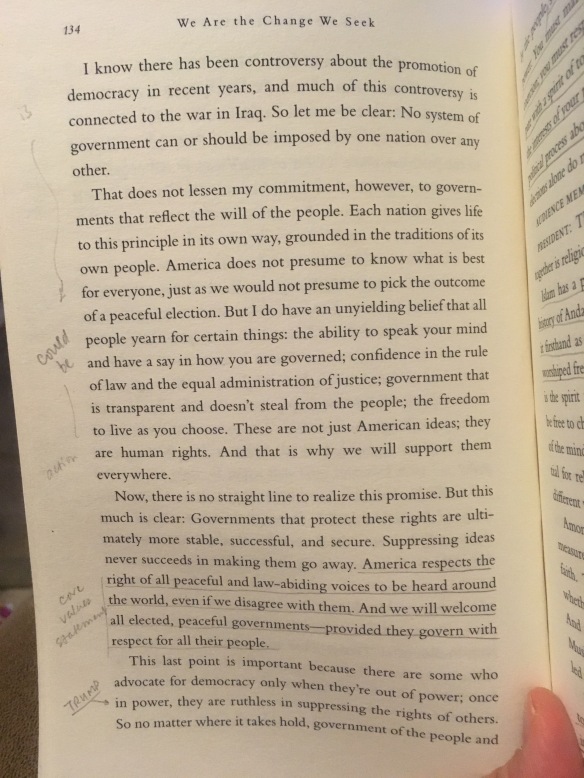

We all need our tribes. Belonging is an essential human need. To fit in, feel understood and accepted, secure—these are necessary for whole person health. And when our tribes have purpose beyond survival, provide meaning greater than simple self-preservation, our membership feels that much more valuable to us. But what happens when tribes pit themselves against one another? How are we all harmed when we veer from “We’re great!” toward “They suck”?

Of course I’m thinking now of intra-professional tribalism: Surgery vs. Medicine vs. Anesthesia vs. OB/gyne vs. Psychiatry. Each specialty has its culture and priorities, strengths and focus. Ask any of us in public and we will extol each other’s virtues and profess how we are all needed and equally valuable. Behind closed doors, though, internists will call orthopods dumb carpenters; surgeons describe internists’ stethoscopes as flea collars, and the list of pejoratives goes on. Maybe I’m too cynical? My interactions with colleagues in other fields are usually very professional and friendly—until they are not. I have experienced condescension and outright hostility before. But can I attribute it to tribalism—that general, abstracted “I’m better than you because of what I do” attitude—or to individual assholery? Or maybe those docs are just burned out? As with most things, it’s probably a combination. Based on what my medical students tell me, negative energy between specialties definitely thrives in some corners of our profession. Third year medical students are like foster children rotating between dysfunctional homes of the same extended family—hearing from each why all the others suck.

So what can we do about this? Should we actively police people’s thoughts and words in their private moments? I mean part of feeling “We’re Great!” kind of involves comparing ourselves with others and feeling better than, right? Isn’t some level of competition good for driving innovation and excellence? Should we even embrace this aspect of tribal pride? It certainly does not appear to be diminishing, and I have a feeling it’s just human nature, so probably futile to fight it.

I wonder why we have this need to feel better than. Is it fear? A sense of scarcity? As if there is not enough recognition to go around? Like the pie of appreciation is finite, and if you get more I necessarily get less? Intellectually we recognize that we are all needed, we all contribute. But emotionally somehow we still feel this need to put down, have power over, stand in front. And it’s not just in medicine. I see it in men vs. women, doctors vs. nurses, liberals vs. conservatives, and between racial and ethnic groups. It makes me tired.

But maybe we can manage it better. Maybe we can be more open and honest about our tribal tensions, bring them into the light. Yes, I think surgeons can be arrogant. And that’s okay to a certain extent—it takes a certain level of egotism to cut into people, and when things start going wrong in the OR, I think that trait can help make surgeons decisive and appropriately commanding when necessary. I imagine surgeons get impatient with all the talking we internists engage in. So many words, so little action, they might think. And yet they understand that words are how we communicate with patients, how we foster understanding and trust. Maybe we can all do a better job of acknowledging one another’s strengths and contributions out loud and in front of our peers (and learners). The more we say and hear such things, the more we internalize the ideals.

Tomorrow I get to spend a morning with surgical attendings and residents. I hope to contribute to their learning during my hour long presentation, but I really look forward to my own learning, to expanding my understanding and exposure to parts of my profession that I don’t normally see. I’m humbled at the opportunity, and I will look for more chances to bring together colleagues from divergent fields. If we commit, we can connect our tribes and form a more cohesive profession. That is my dream for future generations of doctors—to be freed from infighting and empowered to collaborate at the highest levels, for the benefit of us all.