In honor of those who lost their lives this past week:

Alton Sterling, Baton Rouge, LA

Philando Castile, Falcon Heights, MN

Brent Thompson, Lorne Ahrens, Patrick Zamarripa, Michael J. Smith, Michael Krol, Dallas, TX

What can I, one person, do, in the face of such tragedy and pain? How can I help?

I write this post to document my personal intentions for living peacefully. Maybe that’s what I’ve been doing all along on this blog—recording the insights, keeping the journal—so I can remind myself of my ideals and aims, when things get confusing and I lose focus.

The way I see it, the temporal juxtaposition of killings on/by ‘both sides’ of the racial divide this past week led to an important shift in the national conversation on race and violence. I know I will not do justice to all the complexities of our issues in one blog post, but I ask your forbearance for my interpretation, as it has led me to greater conviction for what I can do, I, one person.

Listening to Understand

The first step to peace is to get quiet and listen. This is a central practice of Holding the Space. Before we can solve our problems, especially problems between individuals or groups of people, we must slow down and really hear the narratives of all sides. But when tragedy, especially violence between groups, strikes, I usually see and hear more shouting, blaming, and demanding, than listening. At once people stake their positions around an issue, such as racial discrimination or gun control/gun rights. I see words hurled on news and social media pitting one group against another, each claiming the only right opinion.

I think this is why I have not fully embraced movements like Black Lives Matter and Everytown for Gun Safety. To be clear: my values and opinions align with these groups, no doubt. I believe that our country has a long way yet to go, to recognize and reconcile institutional racism and a runaway gun culture. That said, when I claim membership in such a visible umbrella movement, I may be instantly perceived as less open-minded than I am. “She supports Black Lives Matter; she must be anti-police. I can’t talk to her. I can’t tell her why I support cops and I why (her) movement upsets me.” This sentiment, or something akin, may be conscious or unconscious. With the person who feels it (and I do think it’s more of a feeling than a thought), already I have lost an opportunity to hear and learn from ‘the other side.’ When that happens, we both (all) lose. When someone with an opposing view thinks I will not listen, am unwilling to hear them, then what else can they do but shout, blame, and demand? So by not shouting and demanding loudly from my own camp, I leave myself open to approach, and be approached by, anyone. I send an implicit invitation for communication and exchange of ideas.

This is the difference I see in the past week. More than debate over police reform and gun control legislation, I see pleas for increased compassion and understanding. It feels less inflammatory and more contemplative. Finally, the suffering seems to have quieted us, and we seem ready to engage more civilly.

Others have written and spoken about listening this week, more eloquently than I:

Brené Brown, on her Facebook page, July 7:

I believe that healing racism will require honest conversations about race and class privilege – with our friends, our neighbors, our co-workers, our families, and our children. Yes, these are hard, uncomfortable discussions and we can become paralyzed by the fear of saying the wrong thing or being misunderstood. But we have to be braver than we’ve been because the cost of not having these conversations is paid in lives.

Maria Shriver, on her Sunday Paper, July 10:

There are times in life when answers aren’t what we need. We just need to listen. Listen without judgement. Listen to the wails, listen to the fear. Listen to the divide. Sometimes when someone is screaming for answers they are really screaming to be heard, to be acknowledged, to be understood. Sometimes there are no answers to our questions large and small. Sometimes demanding answers won’t get us the answers we need.

Father James Martin, on his Facebook page, July 10, on the Good Samaritan parable; those you despise have something to teach you:

…Not just that we are called to be compassionate to people that we despise, or think we despise, but that people we despise, might help us. They might have something to give us, to teach us. That is, we’re called to the person we hate as someone we need… The Black Lives Matter protestor has something to learn from the Trump supporter. The Trump supporter has something essential to be taught by Hillary Clinton herself. The fundamentalist Christian has something to learn from the same sex couple. The pro-life advocate has something important to be taught by the person who works for Planned Parenthood… Because in times of division, we often think that being kind means telling people that they’re wrong—for their own good, of course. …Telling them that they’re wrong, or that they’re evil, or that they’re not a real American. But the deeper message of the parable is a lot harder… The one you think you hate is about to help you. The one you think is wrong has something to teach you. Upon the person you hate depends your soul. And once you realize this, you cease to hate them, of course. Jesus is telling us once again that there is no ‘other’. There is no person who cannot teach you something. Learn from the one you think you hate. Listen to him. Open your mind to her. That’s your neighbor. So the Good Samaritan (parable) is not just about the good Samaritan who helps. It’s (also) about the man by the side of the road, who receives help from the one he thought he hated.

I shared House Speaker Paul Ryan’s remarks on my Facebook page this week. He used words like respect, compassion, and common humanity. He cautioned against anger that would “send us further into our corners.” He upheld the president as ‘rightfully’ saying justice will be done. I don’t like Paul Ryan, and I don’t particularly trust him. But I posted his words to remind myself that I need to pay attention—to listen—when I hear people I normally oppose, say something I agree with, even if I am skeptical. Otherwise I contribute to perpetuating the divisions that I say I want to heal.

Listening to Heal

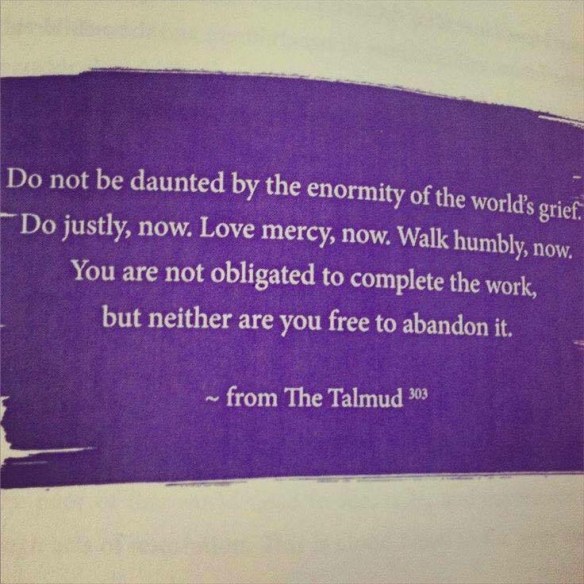

I imagine those who would say that listening is not enough. It will take too long to iron out our differences, if that’s even possible. We need to act, and act now. We demand justice now, gun control now, new laws now, change now, end the violence now! We need boldness, aggressiveness, decisiveness.

I propose that taking time to stop and really listen to our opposition is, in fact, a bold and decisive act. It certainly goes against convention these days. If we said to our protesting and rallying peers, “Wait a minute, maybe they have a point… Maybe we should take a moment and hear them out,” how would most of the group respond? Peer pressure can snuff the flame of inquiry faster than we can imagine. But make no mistake, listening can and does make a difference in real time.

Recall the fabled story of a depressed teenager on his way home from school. He plans to kill himself this day. Somewhere along the way, a classmate approaches, and walks with him. They spend the afternoon in each other’s company, talking, throwing a football, maybe listening to music. The suicidal teen decides to live another day. He feels seen and heard, maybe even understood. Someone has noticed him; he is no longer invisible.

On April 4, 1968, Robert Kennedy made a whole city feel heard. During a presidential campaign stop in Indianapolis, he remarked on the assassination that day of Dr. Martin Luther King.

…Martin Luther King dedicated his life to love and to justice between fellow human beings. He died in the cause of that effort. In this difficult day, in this difficult time for the United States, it’s perhaps well to ask what kind of a nation we are and what direction we want to move in. For those of you who are black — considering the evidence evidently is that there were white people who were responsible — you can be filled with bitterness, and with hatred, and a desire for revenge.

… For those of you who are black and are tempted to fill with — be filled with hatred and mistrust of the injustice of such an act, against all white people, I would only say that I can also feel in my own heart the same kind of feeling. I had a member of my family killed, but he was killed by a white man.

… What we need in the United States is not division; what we need in the United States is not hatred; what we need in the United States is not violence and lawlessness, but is love, and wisdom, and compassion toward one another, and a feeling of justice toward those who still suffer within our country, whether they be white or whether they be black.

So I ask you tonight to return home, to say a prayer for the family of Martin Luther King — yeah, it’s true — but more importantly to say a prayer for our own country, which all of us love — a prayer for understanding and that compassion of which I spoke.

We can do well in this country. We will have difficult times. We’ve had difficult times in the past, but we — and we will have difficult times in the future. It is not the end of violence; it is not the end of lawlessness; and it’s not the end of disorder.

But the vast majority of white people and the vast majority of black people in this country want to live together, want to improve the quality of our life, and want justice for all human beings that abide in our land.

According to his granddaughter Kick Kennedy, 34 American cities rioted that night, but not Indianapolis. It was the only city with a large black population that didn’t. I think this is pretty good evidence for the healing power of listening. It was not an interactive encounter, but Bobby Kennedy aligned himself with the best of people’s hearts that night—and isn’t that the essence of real listening?

We have hard days ahead. I want to help.

I intend to avoid:

-Speaking and writing in sweeping generalizations

-Following snap judgments about groups, or individuals based on their group membership

-Labeling and shaming people or groups as ‘racist,’ ’ignorant,’ ‘stupid,’ ‘lazy,’ etc.

Instead, I resolve to:

-Ask more questions; say things like, “Tell me more…”

-Listen to people’s stories

-Look for what we have in common—shared interests and values, rather than opposing positions

-Practice awareness of my own biases and how they influence my perceptions, words, and actions

I will listen for peace.