NaBloPoMo 2019

On Ozan’s Inner Circle forum today, another member posted about his admiration for Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. It reminded me of a favorite MLK quote, which came to mind on Saturday as I prepared for the Better Angels workshop: “The arc of the moral universe is long but it bends toward justice.” I have referred to this quote many times over the years, and a phrase that I often add goes something like, “Bend that arc! Hang on it with all your might!” Meaning the arc bends toward justice only because we make it so, by working tirelessly for it, by acting visibly in accordance with our core values, and by consistently walking the talk.

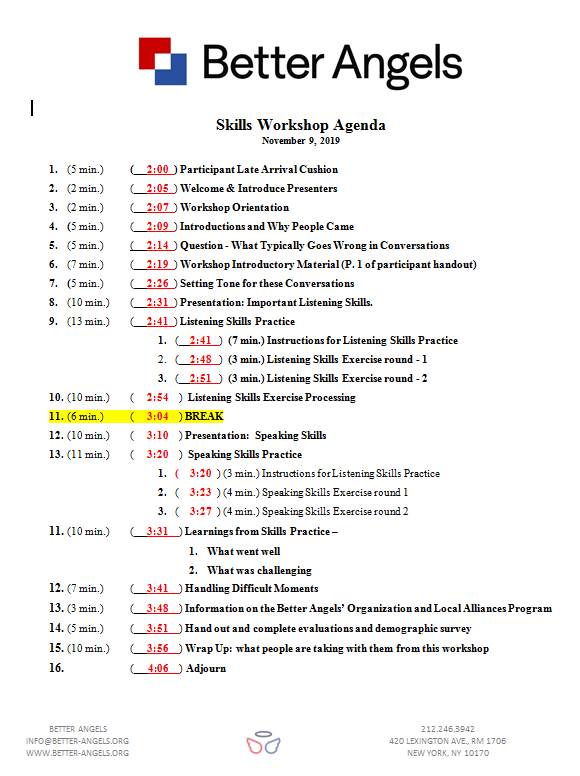

I texted my friend the morning of the workshop: “I’m 90% excited, 10% nervous…Maybe 15%…” Then I thought about the people I know who like the idea(l) of Better Angels, but don’t want to participate. I thought about my friends who express hopelessness at any possibility that people on opposing political sides can ever connect, that we can actually work together across our differences to get things done. I thought about the pushback I might get, that the Better Angels mission is futile, a waste of energy and time. I felt something akin to a tidal wave rise within me, and I texted my friend again, spontaneously, “I intend to make today a day of fierce, infectious optimism.” At that moment I knew my goal that day was to take every example and experience of kindness, connection, empathy, openness, generosity, magnanimity, conviction, and hope, and channel it to the workshop and its participants. Because though it was to be a skills workshop, teaching a way of doing, what we really need are all of the qualities I just listed—they are the way of being that brings the skills to bear in the most meaningful ways.

This idea marinated for a couple of hours while I pictured the venue, reviewed the workshop content, made notes about delivery. I thought again about my friends who feel like our world is crumbling around us, that so much progress made the last century is being eroded. I completely empathize with this perspective, and I understand how it makes us feel we have to fight, to be aggressive and confrontational, to come at the opposition full force, like a bullet train. Do they think listening and speaking skills focused on curiosity and openness too passive and ineffective? Does optimism, the hopefulness and confidence that things will be okay, make me lazy about the issues that matter to me?

Below are the words I texted my friend to describe what I mean by ‘Fierce Optimism’. Normally I would not share such nascent ideas on the blog, but whatever, it’s all an experiment, who knows what better ideas may come from this early sharing?

Fierce Optimism Is:

Urgency with Patience

Or should it read, “Urgency without Impatience”? What I mean here is simply that most things worth doing take a very long time. All important social movements occurred (and continue) over generations. At times confrontation and revolution are necessary. But they are not enough. Consistent, slow, organic, grass roots change on the local level is what sustains consistent progress, keeps it from regressing. The acute urgency I feel to address my deep concerns (for instance, the profound rifts in our relationships) drives me to action. But when that action is directed at another person, I must attune. I have to set realistic expectations for how much I can move this mountain today. Pacing myself, practicing persistence with patience, conserves energy and prevents burnout. It also allows me to look up every once in a while and adjust to my surroundings, adapt to subtle changes, like when someone starts to soften. If I’m bulldozing with strong words and heavy dogma, I am more likely to plow over and through any crack in the door of someone’s mind that might have swung open freely had I taken a more gentle approach.

Strength with Flexibility

Better Angels does not seek to make everybody—anybody—a moderate. Rather, the goal is to hold our positions firmly and with principle, and practice seeing why someone else may hold a different position with equally strong principle. In doing so, two things often happen: First, by challenging our own beliefs and values, we can reinforce them. Telling stories about the experiences that led us to our core values reconnects us with their origins, grounds us in and strengthens our own personal truth. Second, hearing others’ stories helps us broaden our perspective. Most of the time we only see things from our own point of view—this is our default setting. But when we share personal experiences, really learn about each other, the curtains open on a vast landscape of understanding that we may never have imagined. So while I may still hold my goals and objectives firmly, I can more easily release the rigidity of my method, tolerate setbacks with less suffering. Earlier this year I listened to The Warrior Within by John Little. He describes Bruce Lee’s life philosophy, which included a metaphor of the bamboo and the oak. Both are admirably strong, but under intense forces of nature, the oak may break while the bamboo simply bends, sometimes to the ground, but without breaking. Both stay rooted where they are planted, but one is more resilient. Listening with openness and curiosity is not weakness. Allowing for nuance and the possibility that my mind may be changed in some ways, while holding steadfast to my core values, makes me calm, agile, adaptable, and, I think, more effective.

Conviction with Generosity

This is about the assumptions we make. Too often we cast ‘the other’ in abstract as sinister, evil, less than. We hold up the most extreme members of the opposing group as representative of a dull and dumb monolith. We oversimplify and overgeneralize, and then approach any individual we identify as belonging to that group as an assembly line package, a completely known entity. We think we know all about them already, even if we have never met them, just because they identify today as “Red” or “Blue.” In so doing, we make ourselves small. We become exactly as narrow minded and prejudiced as the folks we accuse on the other side. How ironic. Now more than ever, we need generosity. In my mind this encompasses empathy, vulnerability, sincerity, humility and a willingness to allow the complete humanity of every other person, regardless of their political, religious, racial, cultural, or any other persuasion. Conviction without generosity too easily becomes tyranny, for individuals as well as organizations and governments.

*sigh*

Well, like I said, these ideas were just born two days ago. Have I expressed them at all coherently? Have I shown you intuitively apprehensible paradoxes? Can you feel the dynamic balance of agitation and peace? Tension without anxiety? Potential and kinetic energy? If not, that’s okay. I’ll keep working on it. That’s the essential outcome of Fierce Optimism, after all—we keep working, steadily, to bend that arc.