What do you take for granted that you know and do?

How do your conversations with colleagues differ from those with ‘laypeople’?

How does your specific expertise emerge and manifest outside of its own domain?

Friend recently told me about the time his friend offered their Adderall (a stimulant used to treat attention deficit and hyperactivity disorder) for his full body, multi-system allergic reaction to food (which technically constitutes anaphylaxis and should be treated with epinephrine, or at least a strong antihistamine like cetirazine [Zyrtec] or diphenhydramine [Benadryl]). I had immediate, strong, and mixed feelings and thoughts: What? Oh, your friend was trying to be helpful.. and that is absolutely not the right thing.. and omg, what badness could have happened? ANTIHISTAMINES FOR ALLERGIES! And this is why everybody needs an accessible primary care doctor, FFS. Okay, okay, self-regulate. Friend has lived with his allergies for however long, he has apparently handled it fine thus far; this is not my business. Unsolicited medical advice is not often welcome, Chenger, so zip it! And GAAAAAAH, my dear friend, the next time you have an exposure, I pray please for you to have more knowledgeable folks around you! OH that self-restraint really challenges me sometimes.

I share this story as an example of how my doctor mind is always present, always assessing. I felt caring, protective, and concerned when Friend told me, and not at all dismissive or condescending, so I hope that is not how it comes across. All I want is for Friend to be well, to have all he needs for that, and to help if I can, within appropriate boundaries. I hope I respected his boundaries well that day, while still conveying how much I care.

Opioids, anti-inflammatories, corticosteroids, Tylenol–they all address pain, and by different mechanisms, with different side effects, and can be combined and not in certain ways–I know these things. Blood count, chemistries, lipid profiles, iron, B12, CRP, sed rate, TSH–I have ordered and interpreted these and other ‘routine’ blood tests for almost thirty years now. I see patterns for fluctuations, correlates to behaviors, and advise accordingly. Pain, headache, dizziness, nausea, rash, shortness of breath, diarrhea, and myriad other things–I know what’s common and how to treat. I know what to do when I don’t know what’s happening. I know who to call for help. I know how to sit with you, my patient, when things are uncertain and you feel acute distress. I know how to listen beyond the objective answers to my questions. I see you, or at least I do my best. And the longer we know each other, the better I know how to help you, no matter what’s going on. I am an expert at primary care internal medicine.

“Routine,” Orthopod said to me before my knee surgery. I imagine he saw me as a fellow physician and assumed I understood the technical aspects of procedure risk and outcome expectations–which I did. And I was the patient in that scenario, anxious despite my expert medical knowledge, and possibly in part due to it, because I also know how things can go unexpectedly sideways in any operating room. “Routine for you,” I replied. I trusted him, the surgical expert, with my knee and my health. No longer a medical student, and still a learner in a different role, I felt vulnerable and safe. I think we both had a little a-ha moment then.

“Jacob, watch, please? Where does the movement start, again? What is the difference doing it this way versus that way?” In the gym, I am absolutely still a student, though I have been an athlete since adolescence. I have passed the prerequisites of anatomy and physiology. I understand force, mass, and acceleration. And every session, there is still no shortage of new knowledge, experience, and practice to acquire. This is what brings me back so enthusiastically–the more I learn, the more confident I get, and the better I can perform. I make steady progress because my teachers are both knowledgeable and approachable, generous and creative with their instruction.

I wonder what/where/how I might be more willing to study if I had such teachers?

How lucky that throughout my life, I have benefited from so many amazing guides, mentors, and coaches.

In preparation for this post, I listed things at which I am expert, proficient, and novice. Obviously the novice list is longest–humbling and inviting! The proficiency list is gratifying, actually, as I can stand justifiably confident in a variety of diverse skill domains–yay! And when I’m honest, the expert list is remarkably short, which is as it should be.

So it makes me think: How wonderful to be a student of everything, including in my own areas of expertise! Medical knowledge has doubled at least twice since I started training 29 years ago, and that rate continues to accelerate. There is simply too much for any generalist to know, even though we still know a lot and continue to learn about everything. Every time I connect with a specialist colleague, I walk away or hang up smarter and a better doctor for my patients. Bless my colleagues, all!

When I describe my interest in leadership to people, I say that I ‘study’ it. To some, I may seem like an expert. And though I do consider myself advanced in my leadership education, I will always consider myself a student, because every leadership role is unique and fluid. I will never be in a position to not learn and improve. I value humility; when I see it in experts and leaders, I trust them more immediately and implicitly. That is the kind of leader I aspire to be. Learner-leaders cultivate other learner-leaders by example. What an excellent, virtuous cycle!

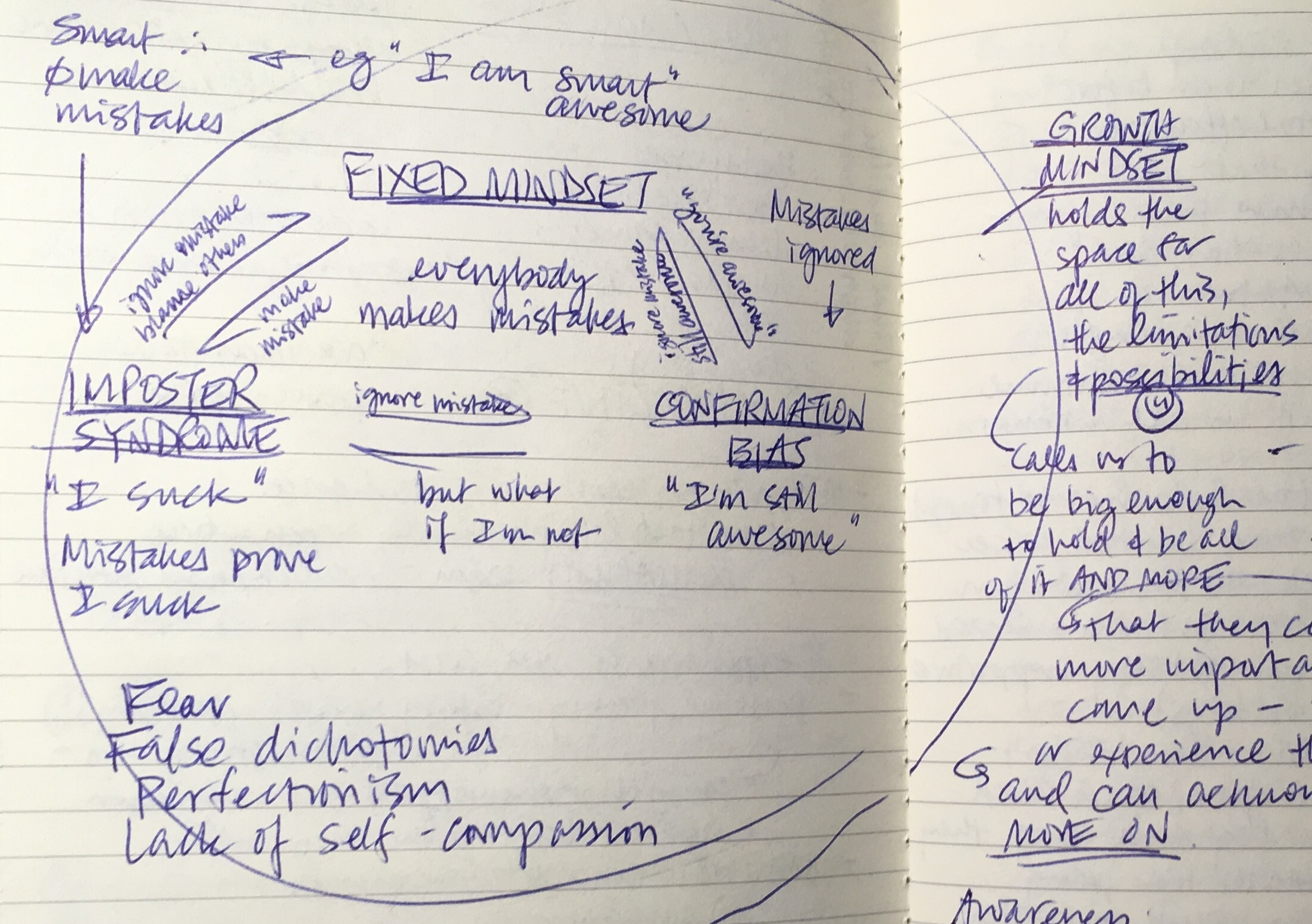

Student mindset is growth mindset, a beginner’s mind. Maintaining it helps me connect more easily with others with whom I may mutually teach and learn from in loving and organic, natural and synergistic reciprocity. It keeps me open and improves, hones my overlapping, intersecting skillsets. It deepens all of my life experiences, inviting contribution from anyone I meet, anything I do. Everything blooms in brighter, more vivid color and texture; every day holds infinite possibility!

I meet experts in multiple domains every day, and I wish I had time to pick all their brains. My morning pages and brain dumps help me process and integrate all of these encounters and more. So much to gain, so many people to meet and love, so much connection in the offing, oh my goodness, it’s just too good!

My wishes for you, dear readers:

May you meet experts who enrich your life by kindly sharing their wealth of knowledge.

May you stand ready to receive their offerings with openness and curiosity.

May you share your treasures of life experience with generosity and humility.

May all of these encounters nourish you, mind, soul, and being.

And may it all make us better for ourselves and one another.

Onward!