In my practice, I focus a lot on stress management. Over the years I have developed a series of questions that facilitate an efficient and productive assessment of stress and its impact on health. I share this approach here.

Meaning to Stress Ratio

- On a scale of 0 to 10, 10 being very high, how high do you rate the overall stress of your work?

- What are the sources of stress?

- On the same scale, 0 to 10, how high do you rate the overall meaning of your work to you? I mean personally, subjectively, regardless of how you think the world perceives your work, how much fulfillment to you yourself get from your work?

- What are the sources of meaning?

Examples of stress sources would be volume, hours, intensity, risk, pressure to perform, and toxic relationships. Examples of meaning sources might include contribution to society, providing for the family, mentoring, supportive relationships, creativity, and intellectual stimulation.

I started asking these questions to patients about seven years ago. I remember the first time I thought to use the trusty 0 to 10 scale to assess stress. It made the conversation instantly faster and more focused. Most people answer the first two questions easily, especially if stress is high. A fair few, however, find the second two much harder. They often get pensive for a moment. This is when I know I might be cracking open an important door in a person’s consciousness—a door that, I believe, leads to important discoveries of self and overall health.

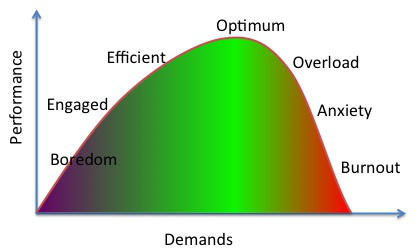

Everybody wants high meaning, low stress. But before we idealize ‘low stress,’ let us remember that all stress is not bad, and some stress is required for motivation, challenge, and productivity.

I soon realized, both for my patients and myself, that both the absolute values of stress and meaning, as well as their ratio, play significant roles in health. Let’s take a look:

Low stress/low meaning : Boredom; disengagement.

High stress/low meaning: A different form of disengagement: Burnout.

Low stress/high meaning: Restlessness: Lack of challenge, looking for something useful to do in service of a cause.

High stress/high meaning: This one is significant. In my interviews, the people who are happiest in their jobs report this combination. The key is that meaning must outrank stress—the meaning:stress ratio must be one or greater—and meaning itself must meet or exceed 6/10. We can tolerate high levels of stress, even for prolonged periods, if we perceive intrinsic value in what we’re doing. It moves the peak of the stress/performance curve to the right. In other words, the stress has to be worth it.

The Three Awareness Questions

- When you are stressed or overwhelmed, where do you feel it in your body? For example, some people get headaches; others feel fatigued. Others get constipated or short of breath/palpitative. Still others notice mood swings and angry outbursts. While we all likely manifest each of these some of the time, most of us have a telltale sign or two that are specific to us.

- What are your existing resilience practices? What do you already do that keeps you from falling off the edge? What keeps you sane on a daily basis? We all have these practices, though it may take some contemplation to identify them. This awareness is important, though, so we may actively monitor. For so many people, exercise is a key stress reliever, and also the first thing cut out of the schedule when life gets busy.

- What are your de-escalation practices? When you feel yourself slipping off the cliff (the headache returns, your bowels grind to a halt), what do you do that brings you back from the edge? Examples here might be physical (running, boxing, or otherwise tantruming), verbal (journaling), or other.

When people make the connection between physical symptoms and subconscious stress, they can let go the fear and dread that often accompanies these chronic and often bothersome sensations. They can use them as smoke alarms—signals to take a step back, look around, and see what is out of balance, smoldering, or actually on fire.

Threat-Challenge-T&B Pie Graph

I previously referenced three major responses to stress here. In summary:

- Threat stress: This is what we generally mean when we say ‘stress.’ It’s the fight, flight, or freeze response, when we sense a treat to survival, or we appraise that we lack the resources to cope with our circumstances. It’s mediated by cortisol.

- Challenge stress: We face a challenge that we feel at least somewhat qualified to tackle but it will be hard, test our limits. If we’re lucky, it’s something we care deeply about and we rise to the occasion—I’m thinking this could lead to a state of flow. This stress results in increases in DHEA and testosterone.

- Tend and befriend stress: This is the Mama Bear response. Under stress, we reach out and protect those around us. We circle the wagons, bring in the kids, make sure everybody’s okay. Oxytocin rises here.

If you were to draw a pie graph representing the proportions of these three stress responses in your work, home, or life in general, what would it look like? All three responses are natural, functional, and serve a purpose. But when threat stress, in particular, becomes chronic and unrelenting, health suffers—we suffer. Fortunately, there are strategies to convert threat stress to challenge stress. Here are some resources for that, if you’re interested:

http://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=1&cad=rja&uact=8&ved=0ahUKEwjklePAq6jMAhUBZiYKHYjRAaMQFggcMAA&url=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.ascd.org%2Fpublications%2Feducational-leadership%2Ffeb14%2Fvol71%2Fnum05%2FConvert-Stress-to-Challenge.aspx&usg=AFQjCNEoBg56lNydHzXTJcXs-9WwoNxmRg&bvm=bv.119745492,d.cWw

https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=4&cad=rja&uact=8&ved=0ahUKEwjklePAq6jMAhUBZiYKHYjRAaMQFggvMAM&url=https%3A%2F%2Fhbr.org%2F2011%2F06%2Fturning-stress-into-an-asset%3Fcm_sp%3DTopics-_-Links-_-Read%2520These%2520First&usg=AFQjCNGCm6kfdy2ElyCRFilRd__NQ3TX8w&bvm=bv.119745492,d.cWw

http://believeperform.com/performance/stress-appraisal-challenge-vs-threat/

This is now the framework with which I interview all patients about ‘stress’ and its impact on their health. It’s my favorite part of the patient encounter. This is when I really get to know a person, and learn, from every encounter, how people experience life. I’ve said it before and I’ll say it again: It’s a tremendous privilege to be allowed into people’s lives so intimately. My job is to help people live their best lives. In the hectic culture of the twenty-first century, we cannot underestimate the importance of stress management in that endeavor.