NaBloPoMo 2017: Field Notes from a Life in Medicine, Day 8

Funny how I just wrote last night about connecting new dots to old dots. It just happened again tonight! A couple of weeks ago I responded to an online ad for an IVY Ideas Night with David Litt, author of Thanks Obama: My Hopey, Changey White House Years, entitled, “How to Inspire, Persuade, and Entertain.” Litt was a senior speechwriter for President Obama, so I thought I could learn new tips for presentations, and feel a little closer to the president whom I miss so much.

I’ve done public speaking since eighth grade, when our speech teacher first taught us abdominal breathing and I discovered the thrill of holding the attention of a room full of people with only my words. I work at an academic medical center and I hold zero publications, but my CV documents over 10 years of professional presentations to various audiences. I thought I was pretty good at this speaking thing.

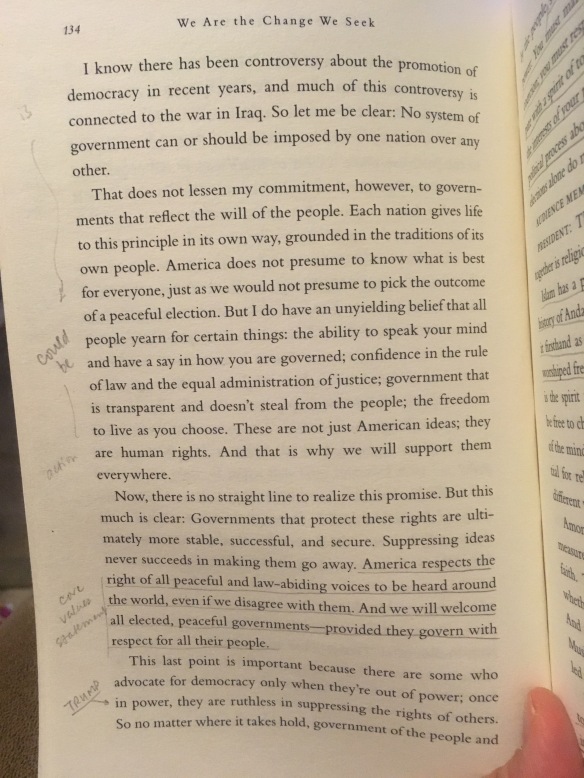

Three years ago I came across this TED talk by Nancy Duarte, whose ‘secret structure’ of great presentations I have used since I subsequently read her book, Resonate. Essentially, she recommends that we invite audiences on adventure stories, create active tension between what is and what could be, and most importantly, make the audience the hero. I have done this better and worse since then, but I always recognize the framework when I see it. Those familiar with this blog know that I am also a fan of Simon Sinek, whose central message is that we perform at our best when we are crystal clear about our Why. “People don’t buy what you do, they buy Why you do it,” he says. Barack Obama employs both authors’ principles with eloquence and finesse, which I noticed reading We Are The Change We Seek, a collection of his speeches as president. The best speeches delivered in this construction create audiences who are inspired, motivated, and empowered to hail a meaningful call to action.

That’s basically what David Litt conveyed tonight. When asked what advice he was given that served him best, he said, “Imagine someone in your audience will tell their friend tomorrow about your talk. What is the one thing you want them to say about it?” What is the Why of your talk? Even though he no longer writes speeches for the most powerful person in the world, he expressed a desire to continue inspiring, empowering, and promoting personal agency in all whom his work touches. Make each and every audience member their own hero.

It turns out, however, that this approach applies to much more than public speaking. On my 50 hour, 500 mile, aspen-pursuing weekend in Colorado last month, I described to my dear friend my favorite moments at work. At the end of a patient’s day-long physical, after I have spent 90 minutes listening to their stories of weight gain and loss, work transitions and complex family dynamics, and reviewing their biometrics and blood test results, I meet with them for an additional 30 minutes to debrief. This is when I present an integrated action plan compiled by the nutritionist, exercise physiologist, and myself. It is a bulleted summary of our conversations throughout the day, centered on the patient’s core values and self-determined short and long term health goals, and crafted with their full participation. I get to reflect back to my patients all that I see them doing well, and shine light on areas for potential improvement. It’s an opportunity to explore the possible—to Aim High, Aim Higher, as the United States Air Force exhorts. I often present the plan with phrases like, “Strong work!” “You’ got this,” and “Can’t wait to see what the coming year brings!” My friend turned to me as we wound through autumn gold in the Rocky Mountains, a bit tearfully, and said, “You make them the hero of their own story.” Yeah, I do, I thought, and I got a little teary, too.

Words are powerful. They are our primary tool for relating to each other, for making another person feel seen, heard, understood, accepted, and loved. You don’t have to be a public speaker or a presidential speechwriter to make a positive difference with your words. At work, in your family, with your friends, with people on the street and in the elevator—what is the one thing you want someone to remember from their encounter with you?